This articles highlights the key research I conducted and contributed to a broader working paper during my tenure at MIT’s Media Lab in 2017. The full paper can be accessed here and examines the current alternative technological methodologies employed by credit providers (lenders) and intelligence providers (analysts), the limitations of their business models and challenges that they face, and then seeks to identify potential visions of the future for credit provision to consumers on a global scale. The full paper is reproduced with kind permission of co-authors Omosalewa Adeyemi and Raunak Mittal.

What Alternative Methods can be Used to Assess Creditworthiness, and What are the Barriers Preventing More Open Access to Lending?

Abstract

In 2014, the World Bank estimated that 2 billion adults in the world lacked access to a transaction account and are excluded from the formal financial system. In conjunction with public and private sector partners, the World Bank Group set a target to achieve ‘Universal Financial Access’ (UFA) by 2020. The goal of UFA is for adults globally to have access to a transaction account or electronic instrument to store money, send, and receive payments by 2020.

While the implementation of UFA would represent a significant step forward for low income and underbanked populations around the world, the enormous potential of mass-market consumers to drive economic growth in emerging countries has been barely tapped. Consumer financial services can help raise the low income population – in developing and developed economies – out of poverty, however there is a significant barrier to opening access to credit to the due to the high customer acquisition cost faced by traditional for-profit lenders.

In this paper, we look at the current alternative technological methodologies employed by credit providers (lenders) and intelligence providers (analysts), the limitations of their business models and challenges that they face, and then seek to identify potential visions of the future for credit provision to consumers on a global scale.

Introduction

Current credit provision solutions barely scratch the surface when it comes to addressing the needs of low-income and unbanked populations in developed and developing economies. While growth in developing economies has been happening faster than in developed economies, financial services at the individual consumer level are struggling to catch up. Despite the hype surrounding micro-finance in recent years, a large number of low-income communities still have no access to formal sources of credit.

The key barrier to fully opening access to credit to the poor and unbanked is the high customer acquisition cost faced by traditional for-profit lenders. Conducting background checks and adhering to “know your customer” (KYC) standards is labor intensive – due to a lack of customer information for risk assessment – and regulations in many countries require credit providers to undertake detailed customer identity verification even for small transactions[1].

Nonetheless, there exists an enormous potential market if banks and other financial institutions are able to embrace financial inclusion of the poor and underbanked. Despite the significant upfront costs and challenges, we argue that institutions should seek to harness this long-term potential – utilizing advances in technology and government stimuli – to offer not only payment and remittance solutions, but access to a wider range of financial products and services.

In this paper, we look at the current alternative technological methodologies employed by credit providers (lenders) and intelligence providers (analysts), the limitations of their business models and challenges that they face, and then seek to identify potential visions of the future for credit provision to consumers on a global scale.

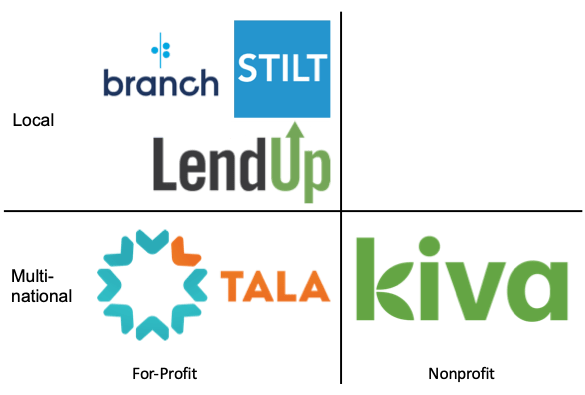

Credit Providers

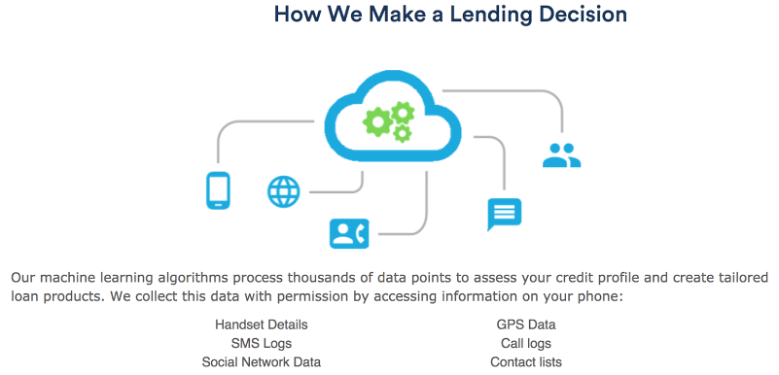

Roughly speaking, existing credit providers can be assessed along two axes: (x) for-profit vs. nonprofit and (y) local vs. multinational. Local for-profit companies operate in one country and have built efficient and (relatively) effective lending products within those markets, utilizing their experience to grow the business. One example, Branch (established in 2015), is based in the USA and Kenya and provides loans to individuals and small business owners based on algorithmic decision-making involving mobile phone data – such as GPS location, call/SMS history and patterns – and battery status. These loans range from $2.50 to $500[2] and require a mobile money account to receive funds and make repayments. In common with most credit providers, borrowers can build a credit profile based on their repayment history in order to access lower interest rates and/or larger loan sizes over time.

Branch faces competition from a number of similar companies (M-Shwari, Saida, Tala, to name a few). Tala (formerly InVenture), an example of a multinational for-profit company, offers credit through its app which claims to utilize over 10,000 data points on each customer’s (borrower’s) phone[3], from financial transactions to daily movements via GPS. Loans range in size from $10 to $500, with an average amount of $50, 11% interest rate and repayment rate of over 90%. To date, ~66% of its 30-day loans have been used for small business purposes[4]. Tala has a presence in the USA and Kenya, and operates throughout East Africa and Southeast Asia, in countries like Tanzania and the Philippines.

Despite the promise of expansion (scaling) across borders, the use of mobile phone data is still somewhat primitive and it remains to be seen if this data alone is a reliable enough indicator of creditworthiness to support a large commercial lending venture. There is also an argument that individuals that have access (i.e. credit means) to regularly use their mobile phones are more likely to favor borrowing from their family and friend network to avoid the high interest rates and strict repayment terms demanded by commercial credit providers.

Figure 1: Example of lending decision process (Source: Branch[5])

Nonprofit and multinational operator Kiva, on the other hand, is active in 83 countries (including the USA) and has provided credit to approximately 2.4M borrowers to date[6]. Unlike Branch and Tala – which have funded themselves through a venture capital backed model – Kiva raises its funding via crowdfunding, targeting philanthropists and social change enthusiasts. Kiva pioneered this model in 2005 and has facilitated approximately $970M of loans to date[7]. Needless to say, this model is not easily scalable on a commercial basis given the need to provide a competitive return to investors.

U.S.-based LendUp is a for-profit venture targeting Americans in the lowest income bracket. It estimates that over half the U.S. population (more than 150M people) has a FICO score below 680, an arbitrary barrier for credit approval within most banks. LendUp offers short-term loans (up to $400 for up to 30 days) at spreads of 15% per month[8] across 24 states[9], allowing borrowers to build a credit history and hence access lower interest rates. LendUp does not provide much detail about the “most technologically advanced credit platform” that they created, but is not the only machine learning algorithm-based lender active in the U.S. Stilt is a 2016 Y Combinator alumnus that is committed to providing access to credit to immigrants within the U.S., hence broadening access to non-U.S. citizens who are effectively locked out of the local credit market.

Unlike the payments space, which is arguably already highly commoditized and multinational in nature, credit provision is typically built on a local model with deep expertise of the market, hence we witness a significantly higher number of local for-profit players.

Figure 2: Position of credit providers researched during this project

One current project that could provide a positive roadmap for future credit provision in the developing world is a partnership between Branch and Uber in Kenya. Uber has an incentive to facilitate access to credit so that its drivers can borrow towards a car, and in return provides its drivers’ data to Branch to assess creditworthiness[10]. All a driver needs to do to access a loan (initially KSh 30,000 or ~USD300) is to complete a minimum of 500 trips and have a 4.6* rating on the Uber app. Starter loans are repayable within 6 months at a monthly rate equating to 1.2%. The combination of new data and a (relatively) low interest rate makes this a compelling case study for future collaboration between commercial and financial institutions.

Additional (and reliable) data sources such as Uber driver information represent an exciting development in how future credit scoring might occur. A key requirement for opening access to credit to a more competitive market will be enabling such data to be available to a wider audience, beyond the individual user case for which the dataset was originally created. Richer digital data – via sources such as mobile phone usage – that can be analysed and employed as an informal ‘credit indicator’ can reduce the complexity of creditworthiness assessment and improve banks’ abilities to deliver services to a wider market[11].

Research / Interviews Conducted – Credit Providers:

- Branch.co :: https://branch.co

- Kiva.org :: https://www.kiva.org

- LendUp :: https://www.lendup.com

- Stilt.co :: https://www.stilt.co

- Tala.co :: http://tala.co

Intelligence Providers

While the availability of funds to lend is obviously a key requirement of an alternative credit provision model, the ability to make informed decisions about credit decisions – and, hence, provide a sustainable business model for commercial lenders – is perhaps the most critical part of the equation. By definition, ‘intelligence providers’ (assuming they are not also lenders) can scale their operations more easily across borders, and most typically work in several geographies, tailoring their product offering according to local requirements.

In this section we examine the current trends between these intelligence providers, broadly along four dimensions:

- Data sources – where does an intelligence provider find its information?

- Interface – how does a partner/consumer interact with the service?

- Partners – who are the end customers?

- Business model – how do the intelligence provider (and its partners) make money?

Data Sources

Mobile phone data remains a key source of alternative data for intelligence providers, especially in emerging markets. U.S.-based Cignifi provides credit and marketing scores for partners such as Telefonica in order to reach underserved population in developing countries. Additionally, social network data and location (GPS) data are more commonly being utilized. Stanford-spinoff Neener Analytics, for example, uses personality and behavior analysis looking at a consumer’s social media footprint to score financial risk for thin-file, no-file or challenging consumers (estimated to represent 35-40% of U.S. consumers)[12].

Harvard spin-off EFL Global started with a straightforward psychometric analysis design, but now includes behavioral games in its credit assessment product. Applicants are asked to conduct simulations such as allocating funds to their household budget, which enables EFL to develop deeper insights into financial behavior as well as helping to prevent fraudulent activity on its app.

David Shrier, Managing Director of MIT Connection Science[13], believes that psychometrics and social media analytics have so far proven to be an unreliable measure of creditworthiness for existing fintech startups. A CEO of new MIT spin-off, Distilled Analytics, Inc., Shrier is working with predictive models that are 30-50% better at credit analytics than existing bank methods. Evolving from the findings of Professor Alex Pentland’s[14] studies involving social physics, Distilled Analytics, Inc. is not restricted to analyzing one data source, but is looking to the future and how it can disentangle the many credit indicators which are to be discovered in the masses of data being restored to consumers.

Two recent developments give an insight into the opening up of data ownership and privacy in the U.S. and Europe. In March 2017, the U.S. Senate (subsequently approved by Congress) supported a resolution[15] that paves the way for Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to sell consumers’ browsing histories to third parties. Across the Atlantic, from May 1, 2018, subjects of the European Union will benefit from the introduction of the EU General Data Protection Regulation[16] (GDPR) which includes the right for consumers to obtain electronic copies of any data being held about them from all commercial enterprises within the expanded EU territories covered under the Act. This heralds a huge leap forward for Europeans to access and control the data that is available and being seen by third parties in their decision-making, including the assessment of creditworthiness.

Interface

Intelligence providers in general are using cutting edge tech (data analytics, machine learning, etc.) in their products, whereas smartphone proliferation and reliable Internet access are potential barriers for expanding the service in emerging markets. Neener Analytics is a fully web-based B2B (SaaS) offering, whereas EFL Global allows consumers to take the tests in a supervised environment (with local “innovation”, in India they have someone with a tablet and a scooter to fulfil this purpose) or online via a web app, for example, with scores then being delivered to financial institutions through their API. New York City-based First Access offers a more customizable credit scoring platform for lending institutions in emerging markets which is accessible through their web interface or API.

In summary, there is no common agreement about the most effective interface between consumers (borrowers) and intelligence providers – the preferred model is likely to be a reflection of the technological maturity of the markets in which borrowers are based.

Partners

Financial services companies are, unsurprisingly, the predominant customers of intelligence providers. Traditional banks, credit unions and fintech lenders are all invested in this space, as well as mobile network operators (MNOs), investment companies, traditional credit agencies such as Equifax and retail store chains looking to expand their credit offering to desirable applicants. In most cases, intelligence providers provide an additional layer of credit scoring for its clients, which can be customized over time to complement, and potentially replace, a credit provider’s existing risk scoring model(s).

Due to the different lending criteria and credit models across financial institutions, intelligence providers typically work with their proprietary model (not trusting any dependent variable data from other sources except for pure financial data) and then expand it to incorporate actual data from the host client. MNOs form an important link in the partnership chain, providing access to mobile phone data which is a key component of many credit intelligence algorithms. Partnerships therefore are truly a two-way street, with data provision and scoring capabilities being the main commodities.

Business Model

There is a definite split in how analytics are being monetized, with traditional access fees (per report request, like traditional credit agencies such as Equifax and Experian) being replaced with specific ‘consulting-style’ partnerships between an intelligence provider and e.g. a credit institution and MNO. This reflects the high degree of customization which occurs, as well as a desire to ensure close control over consumer data and risk scoring data (which is treated as a competitive advantage of a lending decision-maker).

This raises two key challenges which exist in the intelligence provider ecosystem:

- How is data ownership and privacy maintained while it is being shared between the various partners?

Based on responses from the intelligence providers we interviewed, there are two key findings. First of all, there will continue to be friction and challenges to overcome between the incumbent banks and financial institutions (with their outdated standards and infrastructure for data privacy) and the advanced (cloud based, distributed, etc.) tech world as long as fintech companies attempt to disrupt the marketplace in new and innovative ways. Second, for most intelligence providers that work across different geographies, there will be a lot of variability in the standards they need to satisfy within their customer base.

Typically, an intelligence provider owns the psychometric data that is created via the borrowers’ interactions with its platform, and the bank or financial institution owns their own data. The bank will send anonymized records that the intelligence provider matches with a non-PII (personally identifiable information) key that has been created on their side. Such a structure allows intelligence providers to work with banks and financial institutions in jurisdictions with more onerous data privacy laws (e.g. Mexico).

Some intelligence providers have been able to make exceptions for countries with very strict regulations, such as where no data can leave the country (e.g. Indonesia). We are aware of a number of such incidents, during which an intelligence provider will establish a totally separate instance of its technology stack in-country in order to comply with regulations. Needless to say, such a setup is likely to result in higher costs being passed to borrowers but does at least provide a workable solution which can be iterated and improved upon.

- How can a consumer’s score(s) be transferred across different lenders/credit providers to enable a truly cross-border solution?

Nova Credit claims its Nova Credit Passport[17] – constructed from credit information and credit proxies (such as cell phone billing receipts and records) – is a truly global solution for immigrants to passport their credit scores on all their moves. Partnering with credit unions and fintech lenders in nine countries[18] they aim to open up ~$600B market in new lending opportunities to this highly educated and high-earning customer segment.

EFL Global has a medium-term plan to allow borrowers to take their EFL scores to other institutions (in the same jurisdiction or across borders), however it is complicated as banks have different lending criteria and credit models which are uniquely catered to by EFL’s one-to-one consulting services, making a generic product less valuable to individual lenders.

Research / Interviews Conducted – Intelligence Providers

- Cignifi :: http://cignifi.com

- Distilled Analytics :: http://www.distilledanalytics.com

- EFL Global :: https://www.eflglobal.com

- First Access :: https://www.firstaccessmarket.com

- Neener Analytics :: http://www.neeneranalytics.com

- Nova Credit :: https://www.neednova.com

How Might the Future Look

One intelligence provider we interviewed is already working on chatbot technology to enable an “anthropomorphized credit agent” with better UX (to help build trust and get more accurate answers), dynamic calling (no need to download an app, which is important in many emerging markets with limited data capacity) that can integrate with existing platforms (e.g. via SMS). We also heard consistently that mobile operating networks (MONs) are “sitting on goldmines” given the data they have (calls, top up history, messaging frequency, etc.), hence are likely to become a powerhouse of credit scoring data in the future.

Governmental initiatives like GDRP and the proliferation of IoT devices in the home and wider community will contribute more and more data and place it in the hands of consumers. While the opening up of personal data will introduce profound consequences for how we are perceived in a wide variety of settings – a topic that digital reputation visionary, Michael Fertik, explores exhaustively in his book ‘The Reputation Economy’[19] – it also offers a unique ability for the financial services sector to reinvent itself.

New technologies are in the pipeline that promise access to the large numbers of low-income and unbanked global communities in the future digital financial services marketplace.

Future banks and financial institutions (or however else they may be named) will eschew a central bank data repository, easily compromised, in favor of a secure, encrypted distributed data system. Personal data stores not only permit better digital walleting, but also greater security around personal biometric data which is integral to a future bank’s security protocols[20].

The adoption of digital currencies and distributed ledger techniques serves to drive down the ingrained financial transaction costs inherent in the current banking system whilst mitigating operational risks, which will offer financial incentives to future lenders to include low-income and unbanked populations, thus promoting financial inclusion on a global scale.

We expect AI to play a central role in the mission to disentangle indicators of intent from the masses of data being restored to consumers. Shrier, again, believes AI will enable ‘data monetization agents’ that can analyze individual consumer data in real-time and sell insights to the highest bidder(s) – think about breaking a shoelace as you go for a jog and being shown four advertisements for replacements when you look at your communication device – in order to provide a customized and beneficial service to individual consumers.

Such developments could easily serve to widen the financial inclusion gap between developed and developing economies as long as returns for commercial lending ventures are higher in regions where access to credit is already abundant. This raises the question of where there is a stronger appetite to adopt revolutionary technologies like digital currencies and share personal data to a wider audience – arguably this is higher in markets where there is no workable alternative in place today.

In any case, formal governance mechanisms will become increasingly important in order to overcome trust issues and promote the adoption of emerging technology. Governments and regulators should also work to ensure that consumer financial services are growing in developing economies, such that financial institutions of the future can eradicate poverty and harness the long-term benefits of this enormous potential client market.

[1] World Economic Forum Insight Report, ‘Redefining the Emerging Market Opportunity’, 2012

[2] https://branch.co/how_we_work. Accessed May 15, 2017

[3] http://tala.co/about/. Accessed May 15, 2017

[4] https://medium.com/tala/the-future-of-finance-starts-with-trust-bfa79f05893a. Published February 22, 2017

[5] https://branch.co/how_we_work. Accessed May 15, 2017

[6] https://www.kiva.org/about. Accessed May 15, 2017

[7] https://www.kiva.org/about. Accessed May 15, 2017

[8] https://www.lendup.com/rates-and-notices. Accessed May 15, 2017

[9] https://www.lendup.com/faq. Accessed May 15, 2017

[10] http://www.techarena.co.ke/2016/11/18/uber-branch-partnership/

[11] World Economic Forum Insight Report, ‘Redefining the Emerging Market Opportunity’, 2012

[12] http://www.neeneranalytics.com/results.html. Accessed May 15, 2017

[13] http://connection.mit.edu/

[14] http://web.media.mit.edu/~sandy/

[15] Senate Joint Resolution 34 (H. Res. 230): https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-joint-resolution/34

[17] https://www.neednova.com/lenders.html. Accessed May 15, 2017

[18] https://www.neednova.com/about.html. Accessed May 15, 2017

[19] ‘The Reputation Economy: How to Optimize Your Digital Footprint in a World Where Your Reputation Is Your Most Valuable Asset’, Michael Fertik and David Thompson

[20] ‘Frontiers of Financial Technology: Expeditions in future commerce, from blockchain and digital banking to prediction markets and beyond’, Visionary Future publication, David Shrier and Alex Pentland, 2016